So the dust is still settling on DV2023 but it has been, in some ways, a disastrous ending to what was looking to be a well managed year. The government can claim it as a “win” because they filled the global quotas, applied the regional quotas, and despite some embassies who refused to give DV cases a fair chance, the government achieved their goals. Remember the government don’t know us personally, they are not interested in the hardship stories – they simply want to issue the visas and run the program.

But the outcome of DV2023 also caused a tremendous amount of hardship and pain for literally thousands of people.

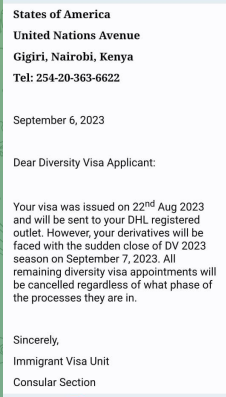

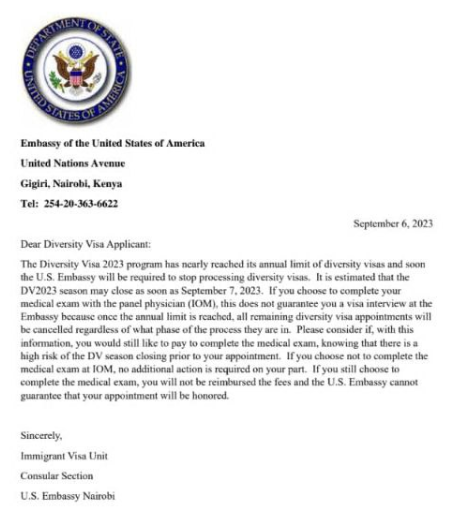

So what happened. On September 6th we started to hear from people about the embassies saying the cap being close to being hit and in some cases people were asked to get to the embassies immediately so they could be issued with visas. We heard stories such as COs rushing through interviews and saying they wanted to finish quickly and allocate the visa to the case because they could be gone at any moment. All this activity was happening very early in the morning in my timezone (California), but I happened to have been online early that morning. Nairobi embassy (ironically an embassy that was one of the worst in DV2023) started informing people of the visa shortage in writing. There was for instance a case where the principal had been issued, but the embassy was warning the derivatives on the case would miss out because the cap would be hit on the 7th. Other messages told a similar story, and we began to hear the same thing from other embassies.

And then on September 6th (still morning in the my timezone) the government issued a public notice on their website that said that they had issued over 54000 DV visas by the previous day, and expected to hit the cap (which they incorrectly gave as 54833) before the end of the fiscal year – possibly as early as the 7th September. Xarthisius scanned the data a couple of times during the 6th and confirmed the cap was being rapidly approached. It’s important to remember that this wasn’t a surprise – the fact that 55,000 number would be reached was something we had known since mid July because there was no reason to schedule cases in September. The only unknown at that time in July was whether the government intended to try and stop issuing at or near the cap, or whether they would allow the cap to be exceeded.

Then as soon as the embassies started receiving scheduled selectees on the morning of Thursday September 7th, the selectees were turned away, the embassies saying the cap had been reached. This was happening late at night in my timezone, the bad news starting from Kathmandu, Nepal and Tashkent, Uzbekistan and moving West to other countries as the sun rose. In fact the government had closed the program on the evening of the 6th. The announcement saying they were nearing the end was just for show.

In the end the CEAC data shows they issued just over 55,000 visas through consular processing, and once the AOS numbers are added in the year will show around 56,000 issuances.

So – why did this happen, and will it happen again.

To understand what went on, we have to look at the recent history and try to figure out why the government did what they did. We have to put ourselves in their shoes, and whilst we can only speculate, I think it is fairly clear why they behaved this way in DV2022 and DV2023. So let me give you my perspective – which I stress is only the perspective of a non lawyer and there is much that happens that we don’t know.

In DV2020 and DV2021 there were some necessary and successful group lawsuits against the government and the government spent a lot of time and money fighting those lawsuits. They are still fighting the largest of those group lawsuits via appeals and as of the time of writing we don’t know the final outcome. The lawsuits were successful in that Judge Mehta agreed the government had a responsibility to run the program to the best of their ability, although he stopped short of ruling the government were required to issue all visas each year. In a win for the DV community, Judge Mehta gave some relief by holding some visas open to be issued at a later date. The government appealed the ruling because, I believe wanted to fight two key points. They wanted to protect the idea that the President could shut down issuance of visas as well as entry, and they wanted to protect the idea that the fiscal year end was a hard date.

However, once there were lawyers who had tasted blood of victory against the government, some of those lawyers (a small number) developed a business model around DV lottery filing some group lawsuits in DV2022 and a number of individual mandamus lawsuits. Though mostly unsuccessful in the group lawsuits, the individual mandamus lawsuits were particularly attractive to people on consular processing cases (waiting for scheduling and 221g). Someone in that frustrating position while be easily persuaded to use a lawsuit if they can afford it, and whilst the lawsuits were not not extremely effective, in my opinion (although that is hard to prove one way or another) they became fairly common during DV2022.

I’m sure I will get some pushback on the not effective comment, so let me clarify. No lawsuits that I am aware of managed to get someone scheduled out of their turn. If someone was in an EV queue with 1000 people in front of them, those cases did not suddenly jump ahead of everyone else. Then there were some lawsuits on 221g cases where the case was decided “apparently” because of the lawsuit. In my opinion, that might have been because of the lawsuit, or it might have been because the case was ready to be issued anyway, meaning timing coincided well with the lawsuit. That is why it is difficult to assess with certainty.

But anyway the sheer number of mandamus lawsuits must have been a headache for the government. Every mandamus lawsuit has to be answered and the government lawyers were spread thin in answering these cases. The government even started using templated arguments from one case to another. The lawsuits all complained that the government was neglecting their duty to process these DV cases.

So the government found a way to nullify the lawsuits – they went “crazy” and started scheduling as many cases as they could in August and September. Essentially they threw caution to the wind and created two record breaking months of interviewing and issuing activity (whereas they had done pretty much nothing in the first 3 or 4 months of the year). The last minute chaos gave us the loss of control that caused the over issuance through a combination of just over 54K visas issued on CP (controlled by DoS) and over 1400 AOS issuances (USCIS). The AOS number was unusually high. The final tally was 55,882 visas issued between CP and AOS.

So then that brings us to DV2023. The government got off to a good start in DV2023. By the time we took the first look at the CEAC data in January 2023, the government had already scheduled nearly 18,000 people and issued 5000. In DV2022 those numbers were 3000 scheduled and 200 issued – a big difference. Everything was going fine, with scheduling and issuances going well. By early July, the August interviews were scheduled and I was satisfied that the government had put themselves into a great position to smoothly run the program and get close to the cap in a much more orderly way than DV2022. I was thinking most interviewing would be completed by the end of August, leaving September to clear up as many 221g cases as possible. I speculated that we would see maybe 500 or 1000 more people being scheduled for September based on the VB movement in OC and SA, and to just be “sure” they would have enough people to use the visas. They were at about 69300 people scheduled, which is pretty much what is needed to get the 55k visas issued.

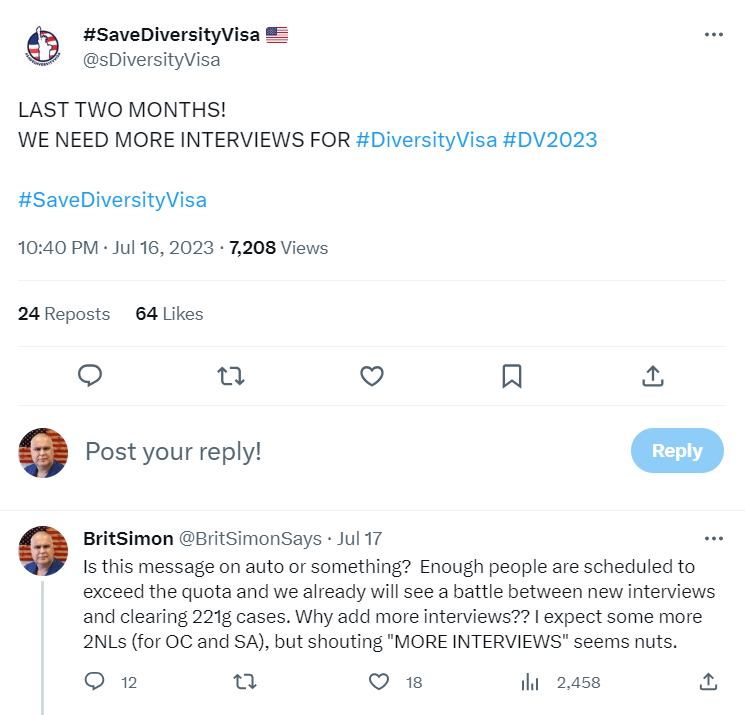

But then they went nuts. They started sending more and more 2NLs for September interviews. Instead of my 500 to 1000 number they actually scheduled 6000 more people. This was madness as far as I was concerned, and I was very clear to all that this was creating a difficult decision. They would either have to exceed the cap by a lot, OR cancel interviews in September. It also put at risk the people still clearing through 221G – well over 5000 people in that status. I was very frustrated at what I saw happening and made my thoughts known in various writings, videos and tweets as in this tweet from July 17 (which I list to show the timeline of when things were clear to me).

So – it was clear to me that the government was creating a crisis, why wasn’t it clear to them?

Well here is my answer. The strategy they have employed achieves their goal. They cannot be criticized for not doing enough. It’s pointless to sue them when they are doing this much work. So they save themselves the considerable effort they were spending in fighting many lawsuits.

The price is paid though by the thousands of people who were told they would have an interview in September. Many had completed their medicals at considerable costs, and that money is wasted. Many had been waiting in 221g for months, having paid their fees and medical costs. All these people with hopes and dreams only to find the door slammed in their faces. It’s heartbreaking.

Unfortunately this is probably the new normal for a while. The government will probably continue to over select (I’ll explain why in another article), and they will probably over schedule in September just as they did this year. We must be more aware of that and make sure that people understand the risks of interviews scheduled in the final weeks. People can at least be made aware of the situation and whilst many have not believed what I was saying since July, I think people will now listen more carefully and put aside their wishful thinking.

So I hope this article has helped you understand what is happening. It’s just my opinion and certainly not written to offend or upset anyone. Much of this can only be written with the benefit of hindsight – I’m sure no one intended for the situation to cause so much pain and anguish. Hopefully the government themselves will read this and be more cautious in their September scheduling. They have the same data we have. We could see what was happening – so could the government. Please.

September 9, 2023 at 14:14

The next entry 2025 they should include providing degrees/mariage certificate… . Why? Because most of winners are ineligible entrants they either have vocational school degree or even not a sigle diploma. They block eligible entrants to win and block them also to get an interview soon.

September 9, 2023 at 14:30

Is it possible for me with a vocational certificate to get a visa?

September 9, 2023 at 16:25

https://britsimonsays.com/education-or-work-experience-qualifying-for-the-dv-lottery/

September 14, 2023 at 05:43

are there any information about DV2025 registration period?

September 14, 2023 at 18:54

It opens on October 4.

September 20, 2023 at 03:33

When will it end?

September 20, 2023 at 09:32

The end will be about 5 weeks later, but the date has not been published yet.

September 14, 2023 at 11:41

I’m sure the chaos will continue largely in dv2024 because, lets take africa region for example. Imagine, if there was a chaos while the highest CN was AF63500, there is no reson it will reoccure when the CN is doubled to AF 122K, Because in both cases the total allowed visa number os the same 55,000.

September 14, 2023 at 11:43

I mean there is no reason it wont reoccure when the highest CN is doubled

September 14, 2023 at 18:58

The point is not the case numbers, it’s the number of selectees and the embassy behavior.

September 28, 2023 at 23:37

Hi Simon

wishing you all the best and thanking you for all your good work and time.

I am a dv24 winner from Colombo and have this question for you.

My family name when spelt in English (this issue doesn’t arise in my native language ) is sometimes spelt ending in the letter “a” and sometimes ending in letter “e”( this is just a difference of one letter and when pronounced they sound the same) , In majority of my documents I have spelt ending in letter “A” including my passport and all other documents , however recently it drew my attention that my parents have been using the ending in ” E” in their Passports. when filling DS 260 there was a section to fill parents details and I filled exactly as is in their passports.

I am the winner and my parents are not included in my visa application , can this be an issue?

My birth certificate is in my native language so this won’t arise there.

this is due to my native language and English syllables, My question will the US embassy regard this as a very minor issue ?

September 29, 2023 at 13:37

It should not be a problem. Your legal name should be from your birth cert and passport, and it is possible for parents to have a different name.

October 5, 2023 at 02:04

Thanks Simon , I also see that my name is spelt differently (just one letter difference) in my OL and AL certificate and I see that getting a change from the awarding body is quite expensive and complicated , I also hope to pass interview through my 5 year work experience and university degree not by AL.

I have the option of getting an affidavit from an attorney stating that I am the same person but many people in my country advise me against this and ask me to change name.

looking for your insight and thanking you

October 5, 2023 at 09:20

You don’t need to correct the certificates. The name is established by your birth cert and passport. Get an affidavit if you want.

October 22, 2023 at 15:54

Hi Britsimon.My dad is trying to se vissa status 2024EU000062XX and he told me I put with zero and with no zero but I see invalid visa case number .why this is happening please?